Table of Contents

Brownfield regeneration in the UK. 3

Evaluation of LUHI mitigation by whitening and greening. 8

The Challenge of Change: global patterns, social change and transformation. 13

Planning for change- Urban regeneration projects. 14

Nicosia: Planning for a divided city. 15

Nicosia’s urban development and social characteristics. 15

Nicosia Master Plan: urban regeneration in the historic centre. 16

Housing regeneration: empowering the neighbourhoods. 17

Challenges and future impact. 20

Chapter 4: Neighbourhood regeneration, the case of Oslo.. 22

Chapter 6: Role of participation in management of privatized housing.. 35

Neo-liberal reforms and new forms of management. 35

Affordability and privatisation of housing stock. 37

Selected experiences from the CEE and CIS region. 38

Chapter 7: Local community responses. 42

Local community responses in Sweden. 43

Chapter 8: Community participation and power sharing: lessons from development studies 49

Community participation in development practice and studies. 49

The terms of participation. 50

Conclusion and points for discussion. 52

Chapter 9: Urban planning and the role of participation.. 54

Chapter 10: Housing Regeneration Innovations. 61

Role of regeneration in achieving sustainability of housing innovations. 63

Housing innovation for young academics in Zagreb: a case for regeneration. 64

Introduction

This Reader presents a selection of research papers on housing written by partners involved in the project’s Work Package 2. This is the second issue which illustrates new research topics related to contemporary housing policy and practice, and similarly to the first issue, it explores avenues that the OIKONET network can exploit to benefit other Work Packages such as Participation and Pedagogy.

The Reader is structured into ten chapters as follows:

Chapter 1 discusses urban brownfields regeneration in the UK by reviewing programmes that support and encourage the development of brownfield sites, namely Spatial Planning, Technical Support, Financial Support, and Direct Development.

Chapter 2 examines the phenomenon of urban heat island and how this can be mitigated by the whitening and greening of urban settlement’s outdoor surfaces. The study used CFD software to determine temperature, wind velocity, air pressure and humidity, heat transfer and boundary conditions.

Chapter 3 reviews post-conflict regeneration programmes in the historic centre of Nicosia in Cyprus. It examines Nicosia’s Master Plan by focussing on urban development, social characteristics, urban regeneration, and housing regeneration in two neighbourhoods: Chrysaliniotissa and Taht-el-Kale.

Chapter 4 discusses briefly neighbourhood regeneration in Oslo, Norway, by critiquing the programme’s approach for Inner City East and Groruddalen.

Chapter 5 examines regeneration of multi-family buildings in an old mining community in Zagorje ob Savi, Slovenia. The use of retrofitting measures to improve indoor living comfort is discussed through case studies.

Chapter 6 discusses the challenge of privatised housing management across CEE and CIS countries through work conducted by the Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS). The challenges facing Riga in Latvia are also reviewed. The chapter argues for an active role of residents in the management of their housing.

Chapter 7 examines local community responses to urban planning proposals for housing regeneration. It argues there is a lack of citizen dialogue in planning processes. It presents feedback from a living lab in the suburb of Hammarkullen in Sweden that is focussed on sustainable property management and maintenance.

Chapter 8 discusses development policies directed at community participation and empowerment. It asks if this could potentially lead to a systemic change, and a more responsive and accountable government is part of this effort. Community driven development approaches are used to explain these synergies.

Chapter 9 reviews urban planning and the role of participation in housing using the case of Budapest, Hungary. It examines the models used for urban rehabilitation and the spontaneous changes taking place in Erzsébetváros.

Chapter 10 discusses the concept of housing innovation as an instrument of integrated sustainable urban development. It also examines the requirements for a housing innovation in order to be considered sustainable and affordable. It uses the case of a housing programme for young academics in Zagreb, Croatia. It finally presents sustainability priorities that will support sustainable regeneration.

Chapter 1: Urban brownfield regeneration

Karim Hadjri & Isaiah Oluremi Durosaiye,

Grenfell-Baines Institute of Architecture,

University of Central Lancashire (UCLan), UK.

Introduction

Urban regeneration is informed and driven by the causes and effects of globalization, climate change, the global economic crisis, and lifestyle changes. In Europe, there is currently a pressing demand to redevelop brownfields areas, inner-city heritage sites, post-conflict and post-disaster areas, and large-housing estates. Housing regeneration tools range from large-scale to micro-scale interventions that lead to a complete change to the physical features of neighbourhoods and the life of their residents.

In Europe ‘urban regeneration’ began to develop after the Second World War as a result of post-war decline and destruction. Urban regeneration is understood as urban renewal which involves physical redevelopment of deprived areas or slum clearance within urban areas, fostering investment, enhancing the quality of life of residents, and creating sustainable communities (Couch et al, 2011). Urban regeneration programmes nowadays focus on urban development with the aim to reduce or suppress urban problems and boost economic development and improve social welfare. This also highlights that communities are always the centrepiece of any urban regeneration and continue to be a major concern for all those involved in these processes (McDonald et al, 2009).

The European project CABERNET (Concerted Action on Brownfield and Economic Regeneration Network), states that brownfield regeneration involves the redevelopment of sites that:

- are derelict and underused;

- may have real or perceived contamination problems;

- are mainly in urban developed areas; and

- require intervention to bring them back to beneficial use (Oliver et al., 2005).

Despite these guidelines, there is an ambiguity in the definition, and disparity in the practical use, of the term ‘brownfield regeneration’ across Europe. While the Nordic countries use the term to define contaminated land remediation, the Western European countries usually associate brownfield regeneration with the redevelopment of the built environment (Oliver et al., 2005). Common to these two approaches is the need for the conservation of natural resources, which is a function of a country’s level of economic development. The idea is buttressed by Osman, Frantál, Klusáček, Kunc, and Martinát (2015) who suggest that the major difference in the characteristics of brownfield regeneration between the capitalist West and the post-socialist Eastern European countries is time lag. In Western Europe, the brownfield regeneration phenomenon started in the early 1970s, whereas it was the shift from controlled to market economy that paved the way for this type of capital investment in Eastern Europe in the early 1990s.

A building that has simply reached the end of its useful life may not be fit to continue serving its original purpose, and so may need to be revamped in order to extend its service life. Upgrading and modernisation, as in energy efficiency refurbishment, may well justify the need for brownfield regeneration (Pan & Garmston, 2012). Legislative restriction against expansion into ‘green areas’ may make green planning permit an unattainable choice of urban developers. The urban community itself may be a deterring factor to further expansion into green areas, for cultural heritage, historical, aesthetic or even landmark reasons. All these factors would make the reclamation of unused, unwanted or wasted built and natural environments an obvious path to maintaining socio-economic equilibrium in the society. However, brownfield regeneration is sometimes associated with reclamation of contaminated land, which may be seen by some interest groups as rekindling old industrial ‘crime’ (Thornton, Vanheusden, & Nathanail, 2005). The overarching goal of brownfield regeneration is not just to accomplish the ultimate status of sustainable use of scarce virgin land space for redevelopment, but for the project to be ‘green’ in every aspects of the reconstruction process (Moffat & Hutchings, 2007).

Brownfield regeneration in the UK

In the UK ‘urban regeneration’ emerged after the second world war as a result of post-war decline and destruction. Urban regeneration is understood as urban renewal which involves physical redevelopment of deprived areas or slum clearance within urban areas, fostering investment, enhancing the quality of life of residents, and creating sustainable communities (Couch et al, 2011). This normally has had a tremendous effect on society as a whole. Urban regeneration programmes nowadays focus on urban development with the aim to reduce or suppress urban problems and boost economic development and improve social welfare. This also highlights that communities are always the centre piece of any urban regeneration and continue to be a major concern for all those involved in these processes (McDonald et al, 2009).

Previous UK governments have argued that new development should have “high quality and inclusive design”, brings people together therefore avoiding segregation. As a result, urban spaces are created that “respond to their local context and create or reinforce local distinctiveness” (ODPM, 2005:14-15). The target of 60 per cent of new urban development on brownfield land was achieved in many areas in England. This was partially driven by a number of funding schemes, although none of these were specifically related to brownfield sites per se, but rather to refurbishment of existing buildings. Nevertheless, developers appear to be encouraged to demolish rather than preserve and reuse, which is mainly due to all the remediation work that would be required in brownfield land. (Hadjri et al, 2008)

It is evident that the redevelopment of brownfield land is a fundamental part of the current housing development programmes in the UK. The government has put in place mechanisms and incentives to encourage the re-use of formerly developed land over the use of Greenfield land in order to meet the UK housing supply. Additionally, the development of brownfield sites makes a significant contribution to the regeneration and rejuvenation of deprived and run-down areas in the process. There are issues that lie within the brownfield development process, which are restricting the ability of developers to help the government to meet the housing demand. There are no specific ‘hard’ barriers, which are impeding the development of brownfield land. On the other hand, the ‘soft’ barriers, such as planning permission hurdles represent constraints for the developers to achieve successful development in an efficient manner. The main constraints come in the form of planning, financial, and physical site condition issues; in addition to concerns regarding ownership of brownfield land as well as technical and real or perceived difficulties. (Hadjri et al., 2008)

Additionally, urban regeneration of waterfronts in the UK during the 1980s and 1990s led most notably to conservation and reuse of historic buildings and the protection of local heritage, the provision of better infrastructure and improvement in the environmental conditions of the area (Jones, 1998). The ‘Urban Renaissance’ championed by the Labour Government in the 1990s was seen as a positive approach to inner city problems, but has been criticised for its ‘gentrification’ effects and change to public spaces (Colomb, 2007). The Urban Task Force was set up in 1998 to identify the causes of urban decline in England, and to propose solutions on how to make cities more attractive for living. The work of the task force continued along the urban renaissance concept and proposed over 100 recommendations to improve cities. Some of these were concerned with design excellence, higher densities and brownfield site redevelopment [iii]. Overall, the proposal would allow the creation of sustainable urban realms through social mix, mixed use and high densities. However, its vision of urban liveability was criticised for promoting gentrification, and the nature of urban renewal challenges in England, particularly in relation to the differences between the north and the south-east (Atkinson, 2003).

The redevelopment of brownfield sites in urban centres can help make the best use of existing road infrastructure and public transport, electricity, water supply, sewer, and telephone. However, brownfield sites are regarded as less attractive due to substantial redevelopment costs. There is the ‘extra’ costs incurred when redeveloping brownfields, which vary greatly from site to site. Additional costs can be due to contamination, existing foundations or other unforeseen ground conditions, conservation and planning issues or infrastructure constraints. Hence not all brownfield sites are suitable for redevelopment since the cost of the ‘abnormals’ (contamination, land stability, site clearance) offset the value of potential returns making them developments that are uneconomically feasible (East of England Development Agency, 2005).

There are at least three categories of brownfield redevelopment. Category 1 represents commercially attractive sites with development costs that are sufficiently below the value of the end use therefore ensuring commercial profit to the developer. Category 2 designates the site abnormals that can reduce the required profit margin of redeveloping the site. These only achieve a breakeven situation between costs and profit, hence market interventions are required to make these sites attractive for commercial development. Category 3 represents brownfield sites that erode the profit margin, and surpass the anticipated cost of the new development, which makes the unattractive to the developer unless the government aids the redevelopment. Non-viable sites are often referred to as ‘hardcore sites’ – land that have been vacant for nine or more years. This is because the development constraints are more deep-seated and more expensive to resolve. (East of England Development Agency, 2005; English Partnership, 2003)

Brownfield redevelopment costs may be lower with potential to achieve high value as an end use if used for a soft end use such as open spaces or nature reserves (English Partnership, 2003). The extent of ‘abnormals’ generally require long-term maintenance after redevelopment, making the lifetime costs further erode end-use values. There are cases when the result can be negative which explains the private sector’s lack of interest in developing these sites. In fact the benefits for such sites are more concerned with ecological and environmental protection.

De Sousa (2000) pointed out that developers’ perception of industrial brownfield development led to the assumption that this was less cost-effective than Greenfield development, and that profitability over similar Greenfield residential developments can be achieved with minor policy changes governing housing brownfield projects. Greenfield sites are often cheaper and easier to acquire and develop judged by current housing development practices (Breheny, 1997), which is primarily due to concerns over potential legal liabilities, and a lack of certainty about funding support on brownfield sites (Banister, 1998). Also there is reluctance by financial institutions to invest in unconventional hi-risk developments (Cadman and Topping, 1995). Oliver et al (2005) argued that a combination of ‘sticks’, through taxation on development of Greenfields and ‘carrots’, through financial incentives such as tax relief for brownfield development, can overcome current financial obstacles. In the UK, redevelopment of brownfield land is led largely by the private sector, and government bodies have very little direct involvement with developers. These only act as “regulators” by issuing approvals and legal permissions. There are however specific programmes to support and encourage the development of brownfield sites, which fall into four main categories: Spatial Planning, Technical Support, Financial Support, Direct Development (Denner & Lowe, 1999).

Spatial Planning

The UK current planning system restricts development on Greenfield sites, but promotes brownfield development, due to national, regional and local levels planning policies, where decisions are made on the basis of the local circumstances. Councils are also reluctant to release previously used land particularly for residential purposes (Chevin, 2000). This may be explained by concerned potential developers caused by the complexity of the UK planning system. Redevelopment in such cases can in fact be accelerated by effective participatory planning approaches (Adams & Disberry, 2002). Allocation of new housing development on Greenfield sites is subject to the results of complex ‘sequential test’ (DETR, 2000), where local authorities must ensure that there are no suitable brownfield sites. In any case, local planning authorities should follow the development plan and are ultimately responsible for the assessment of planning decisions on brownfield land. (Ferber & Grimski, 2002, p.110)

Technical Support

Technical support can be both proactive and reactive. Pro-active technical support is evidenced by funding of ‘best practice’ research and development and offering advice to assist in the development of brownfield sites by the national government and private sector. Reactive technical support addresses factors which might hinder brownfield development. Since contamination is one of the major physical and environmental characteristics that could be an obstacle to the re-use of previously developed land, research for improvement for brownfield development is needed (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2001). Confidence building initiatives and measures in collaboration with the financial and property sectors are also useful. Reactive support requires programmes to build awareness of potential developers and financiers, in order to change their perception of brownfield development. Brownfield development contains a major risk due to its inherent problems discussed above. Hence help developers understand liability for contamination of land, and for reviewing the licensing process for land remediation is beneficial.

Financial Support

Grant aid or gap funding are provided as financial support by the public sector to redevelop sites and achieve the social and economic policy objectives. On the other hand, housing gap funding schemes are available to the public sector in order to support regeneration and increase housing supply. Local Authorities, Regional Development Agencies (RDAs), the Welsh Development Agency, Scottish Enterprise and agencies such as English Partnerships provide grants through this scheme for housing-led development to private developers and housing associations (English Partnerships, 2003). More recently, EU competition policy limitations have led to a reduction in government funding for private sector schemes (Ferber & Grimski, 2002). Hence approval from the EU Commission for supporting projects is required before government funding is granted therefore placing strict limitations on the support provided for private sector housing development. This is put the UK government under immense pressure, which led to the 2000 Urban White Paper which recommended that new financial measures are needed to help housing developers offset the costs of remediation, and which ‘tax credit’ are possible. (Ferber & Grimski, 2002)

Direct Development

In the UK direct development projects can be carried out by local authorities and public sector regeneration agencies (Ferber & Grimski, 2002, p.112), from simpler site clearance projects to fully worked up developments. The re-use of the less viable sites namely ‘hardcore’ sites benefit from the UK’s ‘Development platforms’ which are particularly helpful because they provide the developer with an incentive to select sites for redevelopment. Providing support infrastructure within or near the redevelopment area would still require public sector involvement. The government also encourages new sustainable development initiatives. Test sites have been built on brownfield sites in Salford such as the Persimmon Homes. The Peabody Trust is also actively redeveloping brownfield sites in London into housing and mixed use developments.

Conclusion

This chapter reviewed the definition and practice of brownfield regeneration in Europe. It argued that brownfield regeneration is sometimes associated with reclamation of contaminated land. The overarching goal of brownfield regeneration is to ensure that the reconstruction process is sustainable in every way. The review of the UK case on brownfield regeneration revealed that the redevelopment of brownfield land is a fundamental part of the current housing development programmes. The UK government encourages the re-use of formerly developed land over the use of Greenfield land through a number of mechanisms and incentives in order to meet the UK housing supply. These programmes designed to support and encourage the development of brownfield sites are Spatial Planning, Technical Support, Financial Support, and Direct Development.

References

Adams, D & Disberry, A. (2002) Vacant Urban Land: Exploring Ownerships Strategies and Actions, Town Planning Review, 73 (4), Oct. 2002, 395-416.

Atkinson, R. (2003). Misunderstood saviour or vengeful wrecker? The many meanings and problems of gentrification. Urban Studies, 40(12), 2343 – 2350.

Banister, D. (1998). Barriers to the implementation of urban sustainability. International Journal of Environment and Pollution, 10 (1), 65-83.

Breheny, M. (1997). Urban compaction: feasible or acceptable? Cities, 14 (4), 209-217.

Cadman D & Topping R. (1995). Property Development. Spoon, London.

Chevin, D, (2000) The Battle For Brownfield, Building Magazine, 265 (27), 7th July 2000, 18-22.

Colomb, C. (2007). Unpacking new labour’s ‘Urban Renaissance’ agenda: Towards a socially sustainable reurbanization of British cities? Planning Practice & Research, 22(1), 1-24.

Couch, C.; Sykes, O. & Borstinghaus, W. (2011). Thirty years of urban regeneration in Britain, Germany and France: The importance of context and path dependency. Progress in Planning, 75, 1-52.

De Sousa, C (2000). Brownfield Redevelopment versus Greenfield Development: A Private Sector Perspective on the Costs and Risks Associated with Brownfield Redevelopment in the Greater Toronto Area. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 43, PART 6, 831-854.

Denner & Lowe. (1999) Effective regeneration of Brownfield Land in the United Kingdom, paper presented at seminar on Brownfield Regeneration in Duisburg, Germany.

DETR. (2000). Modernising Local Government, The Stationery Office, London

East of England Development Agency. (2005). Brownfield Land Action Plan. Final Report, April 2005.

English Partnerships. (2003b). Beta Housing Gap Funding Scheme Discussion Paper, by English Partnerships, July 2003.

English Partnerships, (2003a). Towards a National Brownfield Strategy, research findings for the Deputy Prime Minister by English Partnerships, September 2003.

Ferber, U & Grimski, D (2002). Brownfields and Redevelopment of Urban Areas, on behalf of CLARINET 2002, published by Austrian Federal Environment Agency.

Hadjri, K., Osmani, M. & Baiche, B., (2008). ‘Reusing brownfield sites for housing development in the UK’. CIB 2008, “Transformation through construction”, Dubai, 15-17 Nov.

Jones, A. (1998). Issues in Waterfront Regeneration: More Sobering Thoughts-A UK Perspective, Planning Practice & Research, 13(4), 433-442.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2001). Obstacles to the Release of Brownfield Sites for Redevelopment, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York, May 2001.

McDonald, S.; Malys, N. & Maliene, V. (2009). Urban regeneration for sustainable communities: A case study. Ukio Technologinis ir Ekonominis Vystymas, 15(1), 49-59.

Moffat, A., & Hutchings, T. (2007). Greening brownfield land Sustainable Brownfield Regeneration: Livable Places for Problem Spaces (pp. 143-176). Retrieved from https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=oGj9r1cImaMC&oi=fnd&pg=PA143&dq=Greening+brownfield+land&ots=iREToImiyy&sig=xibpvBSbtvIAEcjzRTixXfC1iJ4#v=onepage&q=Greening%20brownfield%20land&f=false

Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM). (2005). Planning Policy Statement 1: Delivering Sustainable Development, ODPM, London. pp.14-15.

Oliver, L., Ferber, U., Grimski, D., Millar, K. and Nathanail, P. Oliver, L., Millar, K., Grimski, D., Ferber, U. and Nathanail, P. (eds) (2005). The Scale and Nature of European Brownfields. CABERNET. Proceedings of CABERNET 2005: The International Conference on Managing Urban Land pp. 274-281. Land Quality Press, Nottingham.

Osman, R., Frantál, B., Klusáček, P., Kunc, J., & Martinát, S. (2015). Factors affecting brownfield regeneration in post-socialist space: The case of the Czech Republic. Land Use Policy, 48, 309-316. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.06.003

Pan, W., & Garmston, H. (2012). Compliance with building energy regulations for new-build dwellings. Energy, 48(1), 11-22. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2012.06.048

Thornton, G., Vanheusden, B., & Nathanail, P. (2005). Are incentives for brownfield regeneration sustainable? A comparative survey. Journal for European Environmental & Planning Law, 2(5), 350-374.

Chapter 2: Local urban heat island (LUHI) mitigation by the whitening and greening of the settlement’s surfaces

Sašo Medved, Boris Vidrih, Suzana Domjan,

Laboratory for sustainable technologies in buildings,

Faculty of Mechanical Engineering,

University of Ljubljana (UL), Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Introduction

The replacement of natural ecosystems with the building blocks of the urban environment impacts on the thermal and hydrological balance of the urban environment; especially in dense urban environments such as modern cities. The phenomenon is known as urban heat island (UHI) and accounts for the higher temperatures in cities compared to the suburban or rural areas. Recent research on UHI carried out in Europe indicated different prediction of UHI intensity from slight, around 0.1 °C, to extreme, up to 16 °C (Santamouris, 2007). Higher environmental temperatures in urban areas lead to rise of energy consumption for cooling, increase of peak electricity demand, degradation of air quality and deterioration of thermal stress on residents of urban areas (Fink, 2012, Kolokotroni, 2012, Mishra, 2013, Pantavou, 2011, Santamouris, 2014-B, Sarrat, 2006 and Sun, 2014). The most effective strategies to mitigate UHI are reducing of solar radiation absorptivity of urban environment elements – use of materials with high optical performances, green roofs, urban vegetation and shading and heat sinks. General overview of using materials with high solar reflectance and infrared emittance was presented by Santamouris (2011 and 2014-A). On the smaller scale, local urban heat island (LUHI) can be defined as difference between maximum daily outdoor air temperature in pedestrian zone inside parts of the city like settlements or city parks and boundary conditions. Niachu et al. (2008) found that in the case of greening only the buildings’ envelope, the average decreasing in ambient temperature is 3.7 °C, while in greening all surfaces in street canyon, the value of mitigation increase up to 4.9 °C. Similar results were presented by Šuklje et al. (2013). Diamoudi presented research (2003), that the greening of the atrium, surrounded by buildings can mitigate the extreme daily ambient temperature by up to 0.8 °C. The study of mitigation of LUHI within city parks was presented by Vidrih and Medved (2013). They found that the cooling effect of the park with an area of 2 ha is up to -4.8 °C and concluded that city parks have great potential on reducing the urban heat islands.

Evaluation of LUHI mitigation by whitening and greening

Increasing the albedo of the urban surfaces and replacing built environment with green areas are regarded as the most effective measures for mitigation of LUHI. The efficiency of such measures greatly depends on shape of the settlement. To avoid overrating the mitigation potential urban planning should not be based only on intuition but on scientific approach as well. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) methods for solving temperature, velocity, pressure and concentration 3D fields are commonly used for this purposes. In this section results of such analysis are presented for three urban settlements built inside equal outdoor space area.

Study cases

Three different shapes of urban settlements: row type, chessboard type and atrium type as presented in Figure 1 were analysed. The common for all three settlements presented in Figure 2.1 are equal area of outdoor spaces (140 x 140 m) and total living area of buildings (2156 m2). For each of the settlement’s type three ratios of building height to street width (H/W) were assumed. As the living area is equal for all analysed settlements, H/W ratio is different for each of the settlement type (for row type H/W 0.35; 1.0; 1.75; for chessboard type H/W 0.13; 0.38; 0.65; for atrium type H/W 0.06; 0.19; 0.32). The LUHI of the reference settlements having albedo of the average modern city (0.35) was compared to LUHI in the settlements having increased albedo (0.65), green ground surface areas and fully green surface areas including facades and roofs of the buildings.

Figure 2.1: Floor plan of different settlements built inside equal outdoor space area (X=140 m, Y=140 m) with equal living floor area (2156 m2) analysed in the presented study; H represents high of the building and W width of the street corridor as considered in the study

LUHI were determinate by coupling of two numerical tools: CFD tool ANSYS (ANSYS, 2011) for determination of temperature, velocity, pressure and air humidity three dimensional field and TRNSYS computer code (TRNSYS 16, 2005) for determination of boundary conditions on surfaces of build environment. It was found out that such approach is more convenient because it speeds up CFD calculations especially because it simplifies the long-wave radiation heat transfer between settlement surfaces. Numerical procedure starts with selection of reference summer day for 24 hour numerical simulation. Data from TRY database was used for reference location (the summer day with average outdoor temperature 25.8°C, average humidity 48% and maximum solar radiation on horizontal plane 850 W/m2 was selected for the site with latitude 46° north). Reference wind velocity is taken at 10 m above the ground and 0.3 exponent is assumed for the calculation of wind velocity at different heights. Separate energy balance model were developed for built surfaces, green areas on the ground and green areas on the facade and roofs of the buildings. It was assumed that all green areas have leaf area index LAI equal to 1 and sufficient soil moisture is also assumed to ensure maximum effect of natural cooling.

Results are presented in form of LUHI intensity in Figs. 2 to 4 regarding to different mitigation strategies – for the case of high albedo surfaces (Figure 2.2), for the settlements with green ground area (Figure 2.3) and for the settlements with green ground and build surfaces (Figure 2.4). In all figures LUHI of low albedo settlements are shown in order to facilitate comparison between mitigation strategies.

Figure 2.2: LUHI for different type of settlements and H/W values in case of increasing the albedo of all surfaces in the settlement domain from 0.35 to 0.65 (including ground and building envelope surfaces)

Figure 2.2: LUHI for different type of settlements and H/W values in case of increasing the albedo of all surfaces in the settlement domain from 0.35 to 0.65 (including ground and building envelope surfaces)

Figure 2.3: LUHI for different type of settlements and H/W values in case of greening of the ground of settlement domain

Figure 2.3: LUHI for different type of settlements and H/W values in case of greening of the ground of settlement domain

Figure 2.4: Values of LUHI for different type of settlements and H/W values in case of greening of all surfaces in settlement domain (including ground and building envelope surfaces)

Figure 2.4: Values of LUHI for different type of settlements and H/W values in case of greening of all surfaces in settlement domain (including ground and building envelope surfaces)

From presented results it can be concluded that urban planning process has significant influence on mitigation of local urban heat island which are formed in street canyons. LUHI in common low albedo settlements (dark line in Figure 2.2, Figure 2.3 and Figure 2.4) is much lower in case of LUHI is reduced from 2.5 K to 1 K in atrium type of settlement. H/W ratio has significant influence on LUHI only in case of low reference wind velocity (< 1,5 m/s measured on the settlement domain boundary). LUHI intensity in high albedo settlements (Figure 2.2) are significantly lower, but noticed regardless of the type of the settlement. Nevertheless LUHI is as low as 0.25°C in case of atrium type settlements. As in the previous case, reference wind velocity has minor influence on ULHI intensity if velocity is above 1.5 m/s. It was found out that greening of ground of settlement domain (Figure 2.3) is very effective LUHI mitigation strategy in chess and atrium type of settlements because LUHI is almost eliminated. Even higher influence of the green ground areas can be noticed in case of high rise buildings and low wind speed conditions in row type settlements. In this case green ground areas has cooling potential. From the Figure 2.4 it can be seen that all green settlements have cooling potential regardless of the type as LUHI is negative for all analysed cases. No significant influence of street canyon height to width H/W ratio or reference wind velocity was found leading to conclusion that results can be treated as general roles.

Conclusion

As settlements are core structures of the cities and LUHI as shown in the study could be intense, the mitigation of LUHI has to be taken into consideration in frame of urban as well as global climate change mitigation.

References

ANSYS. (2011). ANSYS FLUENT Release 14.0 User Manual, ANSYS Inc.

Dimoudi, A. and Nikolopoulou, M. (2003). Vegetation in the urban environment: microclimatic analysis and benefits. Energy and Buildings, Vol. 35, 1 (2003), pp. 69-76.

Fink, R., Eržen I. and Medved, S. (2012). Effects of urban pollution on cardiovascular parameters. In: 12th World Congress on Environmental Health, Vilnius, Lithuania, 22-27 May, 2012. New technologies, healthy human being and environment: abstract book. Vilnius: IFEH, p. 63.

Kolokotroni, M., Ren, X., Davies, M. and Mavrogianni, A. (2012). London’s urban heat island: Impact on current and future energy consumption in office buildings. Energy and Buildings, Vol. 47, 4 (2012), pp. 302-311.

Mishra, A. K. and Ramgopal, M. (2013). Field studies on human thermal comfort — an overview. Build Environ, 64 (2013), pp. 94–106.

Niachou, K., Livada, I. and Santamouris, M. (2008). Experimental study of temperature and airflow distribution inside an urban street canyon during hot summer weather conditions. Part II: Airflow analysis. Building and Environment, Vol. 43, 8 (2008), pp. 1393-1403.

Pantavou, K., Theoharatos, G., Mavrakis, A. and Santamouris, M. (2011). Evaluating thermal comfort conditions and health responses during an extremely hot summer in Athens. Build Environ, 46 (2011), pp. 339–344.

Santamouris, M. (2007). Heat island research in Europe: the state of the art. Advance in Build Energy Research, 2007, 1:123.

Santamouris, M. (2011). Using advanced cool materials in the urban built environment to mitigate heat islands and improve thermal comfort conditions. Solar Energy, Vol. 85, 12 (2011), pp. 2085-3102.

Santamouris, M. (2014-A). Cooling the cities – A review of reflective and green roof mitigation technologies to fight heat island and improve comfort in urban environments. Solar Energy, Vol. 103, 5 (2014), pp. 682-703.

Santamouris, M. (2014-B). On the energy impact of urban heat island and global warming on buildings. Energy and Buildings, Vol. 82, 10 (2014), pp. 100-113.

Sarrat, C., Lemonsu, A., Masson, V. and Guedalia, D. (2006). Impact of urban heat island on regional atmospheric pollution. Atmos Environ, 40 (2006), pp. 1743–1758.

Sun, Y. and Augenbroe, G. (2014). Urban heat island effect on energy application studies of office buildings. Energy and Buildings, Vol. 77, 7 (2014), pp. 171-179.

Šuklje, T., Medved, S. and Arkar, C. (2013). An Experimental Study on a Microclimatic Layer of a Bionic Façade Inspired by Vertical Greenery. Journal of Bionic Engineering, Vol. 10, 2 (2013), pp. 177-185.

TRNSYS 16 (2005). Transient System Simulation Tool, Solar Energy Laboratory, University of Wisconsin Madison.

Vidrih, B. and Medved, S. (2013). Multiparametric model of urban park cooling island. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, Vol. 12, 2 (2013), pp. 220-229.

Chapter 3: Post-conflict regeneration in the historic centre of Nicosia: global challenges and local initiatives

Nadia Charalambous

Department of Architecture,

School of Engineering, University of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus.

The Challenge of Change: global patterns, social change and transformation

As the 21st century unfolds, an increasing majority of the world’s population will live in cities. People are drawn to cities as centres of economic activity, innovation, and opportunities for a better life. However, cities are complex entities, which are constantly changing in terms of their built form, their social and demographic make-up, their street network and public spaces as well as the way in which they are used and lived by their population. Multiple, even abrupt changes that cities face today due to globalization, massive internal flows of labour and migration, climate change, economic fluctuations, and terrorism pose challenges of increasing complexity.

An alarming rapid transformation is taking place around the world affecting the majority of cities and their citizens globally, with impacts on the economy, the environment and communities. These impacts are affecting people differently, and are most devastating to those already facing disadvantageous situations within society. The recent patterns of urban segregation and exclusion in cities are discussed in the context of globalization effects, changing forms of production, declining welfare, changing power relations and developing technology (Marcuse & van Kempen, 2000:1), which relates to a more general discussion of societal transformations. Urban social patterns are changing at an increased pace affected by societal and global transformational forces; social changes relate to respective spatial changes such as service-adapted spatial patterns versus manufacturing-based patterns, and central and edge city patterns versus peripheral and traditional ones (ibid). This shows that cities of today are becoming “radically altered” in the sense of their scales, scope and complexity (Ibid.) with respective implications for housing design and supply.

So, while cities are indeed hubs for innovations and investments that may expand opportunities for human wellbeing they need to confront such multiple challenges such as social breakdown, physical collapse or economic deprivation, especially in inner city areas. Mediterranean cities for example are predominantly urban with historic centres experiencing spatial, social and economic deprivation due to suburbanization, political crises, poor infrastructure and lack of resources. Poor housing supply, physical degradation, ageing of the remaining population, large concentrations of ethnic minorities, unemployment and loss of economic activities are often problems faced by such areas.

Urban municipal authorities and policy makers are called to respond to such rapid and simultaneous changes in new and often innovative ways and initiatives. Many of these differ in geographic scale – home, neighbourhood, inner-city and suburbs– and are often criticized for a lack a unifying framework for assessment and intervention. Initial efforts in the 1980s for example, addressed urban problems of historic centres focusing either on the physical or on the economic aspect (Petridou 2003) and have been criticized as being targeted in ad hoc projects without any overall strategic vision and with little consideration on the priorities of the local communities.

Within this framework, urban regeneration approaches appear prominent in addressing such problems and in planning for change, being primarily concerned with the upgrading and reorganization of inner city centres, former industrial areas or housing areas facing periods of decline due to major short- or long-term economic problems, deindustrialization, demographic changes, underinvestment, racial or social tensions, physical deterioration, and physical changes to urban areas.

Planning for change- Urban regeneration projects

Urban deprivation has initially been addressed through economic and planning policies geared towards physical and economic renewal and revitalization of local areas. Recognition that successful regeneration should also incorporate social and environmental policies resulted in a shift from urban renewal and revitalization techniques to a comprehensive urban regeneration approach (Couch 1990). Such a definition of urban regeneration states that it is a comprehensive and integrated vision and action to address urban problems through a lasting improvement in the economic, physical, social and environmental conditions of an area, with a strong emphasis on place-based approaches that links the physical transformation of the built environment with the social transformation of local residents. The outputs of the urban regeneration process can thus be grouped under five headings; neighbourhood strategies, training and education, physical improvements, economic development and environmental action (Roberts, 2000).

The spatial scale of urban regeneration programs and projects vary from local area-based approaches to broad national policies. Different kinds of problems need to be dealt in different spatial levels. Likewise, each policy level should be considered, giving appropriate acknowledgement to other layers of policy both below and above while working on a specific scale. Further challenges are linked to tensions between top-down technical and managerial approaches to urban regeneration and bottom-up or grassroots environmental needs, expectations and initiatives. It is widely accepted that in democratic societies urban regeneration processes should adopt governance approaches that involve multiple stakeholders including residents and other stakeholders, stimulate local economies and prevent displacing problems from one area to another (Roberts and Sykes, 2000). The local authorities must have the power to play a vital role in the regeneration process since they have knowledge of the particular circumstances of their areas and they can act as catalysts and bring together other partners, including housing associations, community groups and the private sector.

Urban regeneration projects and research also need to engage with issues of social cohesion, housing supply, affordability, and the engagement of different groups in the process alongside infrastructure investments such as new roads and public transport, public realm improvements, the provision of building land or properties and refurbishment of existing buildings including housing developments. Possible impacts of housing regeneration strategies in relation to quantity, quality and context of housing growth and the respective demand on local communities are also important concerns.

The need to tackle the interrelated aspects of deprivation in a holistic way, by adopting a comprehensive regeneration approach which includes not only physical and economic aspects but also the social issues of safety, employment, social services, health, training etc. should gradually be acknowledged.

Nowadays there are commonly accepted best practices which do attempt to adopt an integrated and holistic urban regeneration approach through the identification of both the global but also the specific to each case local factors that may have caused deprivation and the understanding of local needs and aspirations. The development of such an approach is a major challenge to authorities, urban designers and relevant stakeholders. Urban regeneration in post conflicts cities such as Nicosia is an even greater challenge.

This article explores housing regeneration projects in the historic centre of Nicosia which attempt to revitalize the deprived areas of the inner city, rebuild physical infrastructure, manage negotiations between the two different/divided parts of the city through the building of commonly accepted institutions, and direct local and external resources towards the real needs of all citizens (Petridou 2007).

Nicosia: Planning for a divided city

Nicosia’s urban development and social characteristics

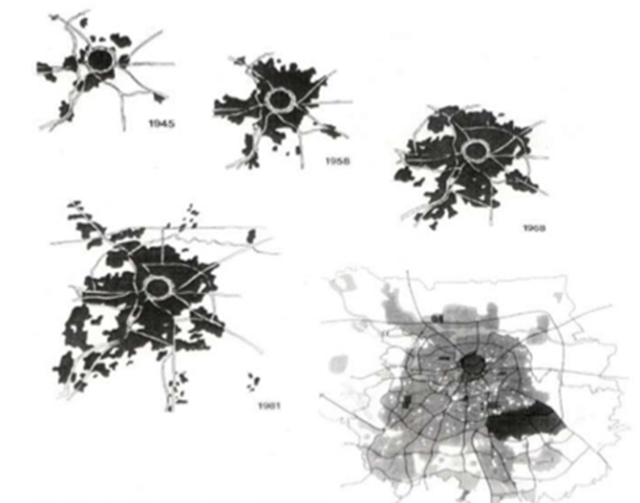

Nicosia has been the capital of Cyprus since the 9th century AD and remains the largest city and the political and administrative centre of the island. Originally the city remained self-contained within Venetian walls until the 1930s when wealthy Greek residents moved to the south of the old town due to public health reasons as by the 1930s the population had grown rapidly causing overcrowding and putting strain on the infrastructure. The post war and post-independence periods saw rapid urban growth in the city where the two ethnic populations that inhabited Nicosia already tended to live in separate areas (the Turkish Cypriots in the northern side of the town and the Greek Cypriots in the southern side).

The city is currently divided east-west by a buffer zone implemented by the United Nations following the 1974 Turkish invasion of northern Cyprus which led to the complete separation of the two major ethnic groups on the island. The southern side of the city is administered by the Nicosia Municipality, while the northern side by the Turkish Municipality of Nicosia – the two have long cooperated not only to maintain the common infrastructure of the city such as the sewerage system but also to develop a planning view of Nicosia as a whole with a first masterplan prepared in 1979, though this was not enacted until 2001.

Figure 3.1: Nicosia’s urban growth (Source: Nicosia Local plan 2003)

Figure 3.1: Nicosia’s urban growth (Source: Nicosia Local plan 2003)

The urban structure of Nicosia can be categorized into four parts:

- The walled city, which is the historical core and, despite the decline following the division, still retains a mix of commercial, service, residential and cultural uses, as well as light industries, especially in workshops along the buffer area. Much of the poorer and immigrant population live in this area, although some investment by wealthier classes in renovated residential historical property has taken place in recent years.

- The buffer zone which cuts across the walled city as well the modern residential areas to the east and west of the historical core.

- Two core business areas, one in the north located just outside Kyrenia Gate, the other in the south centred around Makarios Avenue, but expanding to its east along and to the south of the main ring road running along the south of the old walls.

- Residential areas built before 1974 toward the west and the east of the old town and further residential areas developed after 1974 further beyond the core business areas, which, in the south have come to encompass former villages within the urban sphere of Nicosia.

Since the post war period the southern side of Nicosia has seen further urban growth spreading out towards suburban areas as the old town declined, commercial uses changed their location and local residents moved out (Charalambous et al, 2002). Generally the city has expanded to the north and to the south, avoiding the east-west axis along the buffer area despite the fact that before 1974 development was occurring towards the east and the west. The old town centre has faced a long decline, as it became an area at the edge of the city following the division. However this has recently been revitalized, partly thanks to the Nicosia master plan (Figure 3.2) through which regeneration of the historical residential areas of Taktakalas and Chrysaliniotissa in the south and Arabahmed in the north was funded and partly due to the revitalization of the high street and its surrounding areas following the opening of the check point on Ledras Street, making it a thoroughfare for tourists crossing from one side to the other and also recreating a level of mix for those from the two communities willing to visit the other side (Figure 3.3).

Nicosia Master Plan: urban regeneration in the historic centre

The Nicosia Master Plan, a common flexible master plan for the city, was prepared in 1978 by representatives of the two communities in an attempt to address existing problems while creating an adaptable framework that would facilitate the development of the city as a whole. This framework aimed at the regeneration of the declined city centre, its future local and regional opportunities, and the potential role that this area could assume in the case of reunification.

The masterplan acknowledged that the regeneration policy for the historic centre needed to be approached as a multidimensional process in order to effectively address the environmental, social and economic problems of the walled city (such as the decline in population, loss of commercial activities and employment, large concentrations of migrants mainly due to low rents, high number of vacant properties, absence of private investment and deterioration of its environmental quality). It is described as ‘urban heritage-based regeneration’, adopting cultural tourism and education as the prime movers to stimulate future residential and commercial activity.

Figure 3.2: Nicosia master plan Figure 3.3: Bi-communal projects Nicosia

(Sources: http://www.thepep.org/en/workplan/urban/documents/petridouNycosiamasterplan.pdf)

The proposal incorporated the following objectives (Petridou 2007):

- Social objectives; rehabilitation of old residential neighbourhoods, community development and population increase.

- Economic objectives; revitalization of the commercial core and increase of employment opportunities.

- Architectural objectives; restoration and reuse of individual monuments and of groups of buildings, with significant architectural and environmental qualities.

- Planning objectives; balanced distribution of mixed-use areas and the density of development in relation to the character of the historic centre, improvement of traffic circulation based on pedestrianisation schemes and one-way loops system in order to avoid through traffic.

During the last fifteen years a series of bi-communal projects have been implemented in selected areas on both sides of the historic centre. The objectives elaborated by the Nicosia Master Plan (NMP) for the historic centre have since been implemented through a combination of actions: through the provisions of the Local Plan, through economic incentives given to private owners by the government and through public investment projects.

Housing regeneration: empowering the neighbourhoods

Following the division of the city in two distinct areas, a process of population exchange took place between the Greek and Turkish Cypriot sides. Both sides had to face a great challenge of housing an important number of refugees while dealing at the same time with the properties that were evacuated. Housing rehabilitation and neighbourhood infrastructure was thus high in the agenda of the projects mentioned in the previous section aiming at supporting the creation of an enduring local community.; involved stakeholders supported the argument that housing “rehabilitation can only be achieved as a long-term process only if it refers to social revitalization, involving as its basis the revitalization of population structure, which is the precondition of sustained physical conservation” (Petridou 2007).

Between 1985 and 1990 two important such programs took place in the walled city: the housing programs at the areas of Chrysaliniotissa and Taht-el-Kale. The project in Chrysaliniotissa was part of a twin bi-communal pilot regeneration project (in the quarters of Arab Ahmet -northern part and Chrysaliniotissa – southern part) under the NMP with the support of the UNDP and USAID where the state acquired all the abandoned and derelict buildings and empty plots through compulsory purchase orders. The project in Taht-el-Kale was part of the national policy for the rehousing of refugees, which also provided an effective solution for the provisional usage of evacuated Turkish Cypriot-owned properties. This project was implemented in continuity and complementarity with previous EU-funded projects located in the intervention area, such as the Multifunctional and Children’s Centres, comprising altogether a comprehensive and multidimensional urban development program (AEIDL 2012) .These programs are considered successful since they managed to establish a local community and ensured a balance among the income groups that live in the area[1].

Chrysaliniotissa. The area of Chrysaliniotissa was characterized by neglected status of buildings, low proportion of owner-occupiers, low-income position of both owners/occupiers and tenants, lack of community facilities, lack of economically active residents and a high proportion of aged residents.

The overall objective was to increase the available housing units and the provision of community services, public facilities and commercial uses (such as a kindergarten, artisans workshops, students hostel, and the enhancement of public open space) in order to attract new residents, based on the belief that neighbourhoods need to comprise a mixture of activities which work to strengthen social integration and civic life (Nicosia Master Plan team). Young couples with children were housed in existing repaired traditional buildings allocated according to certain criteria to those willing to reside in the area on a long-term basis. Priority was given to families of previous owners and to people related to the neighbourhood while consideration of their needs and aspirations through their involvement was a major aspect of the process. The project gradually stimulated private investment in the restoration of many listed buildings of the area.

Figure 3.4: Chrysaliniotissa area.

Taht-el-Kale. The project was carried out by the municipality of Nicosia with ERDF support under the OP ‘Sustainable development and Competitiveness 2007-2013’. The technical team of the NMP Office, consisting of architects, planners, civil engineers, quantity surveyors and financial administration officers, designed the project and are responsible for its implementation and management.

The quarter of Taht-el-Kale is located in the south-eastern part of the Venetian walled city; it is one of the traditional neighborhoods of the walled city, situated very near the buffer zone that divides the city in two. As in the case of Chrysaliniotissa, the shrinking and ageing of the population, the lack of open public spaces and the reduction of the productive base are some of the most important problems of the area. A recent population increase, as well as a considerable share of the commercial activity, is due to the settlement of migrants in the broader area who take advantage of the low rent levels. However, in most cases, the housing conditions of migrants and low-income people are very bad. There are also major problems of traffic and accessibility mainly due to the dependency on private cars.

The proposal for the urban regeneration of the area includes housing revitalization, improvement of the physical and built environment of the neighbourhood, restoration of historic buildings and upgrading of public spaces aiming at its broader socio-economic regeneration. The significance of public space is emphasized and it is expected to have a multiplier effect, by enhancing the confidence of the private sector to invest in the area, as well as consolidating the appreciation of local residents for their neighbourhood and thus motivating their further involvement in processes of urban development.

The project mainly consists of restoration of façades and fences of buildings facing the roads; restoration of buildings of significant architectural value; redesign of public spaces and roads in order to improve pedestrian accessibility, particularly for disabled people, including lighting and urban equipment; creation of small public open spaces; rearrangement of common service infrastructure and upgrading of the sewage system and new traffic arrangements. More specifically the project aims at (AEIDL 2012):

- the preservation of the area’s traditional character. In this way the project is expected to act as a catalyst for private initiatives for the rehabilitation and reuse of abandoned buildings.

- the creation of important landmarks of city-wide appeal by redesigning open public spaces (which are very limited in the area) in order to improve the quality of life and strengthen the sense of community and neighbourhood for local residents;

- the future development of the area as an important and lively regenerated urban centre in connection with adjacent neighbourhoods and other important social and cultural spaces which are also part of the overall plan for the revitalisation of the walled city;

- mobilisation of private investment and initiatives for the development of new economic activities, especially third sector initiatives relating to culture and leisure (youth leisure activities, small enterprises compatible with the main residential use of the area, creative sector activities etc.), while also providing new employment opportunities;

- attracting new residents (especially young couples) and economically active social groups, as well as visitors and leisure and touristic activities.

Figure 3.5: The proposal for the urban regeneration of Taht-el-Kale

(Source: http://www.nicosia.org.cy/el-GR/municipality/projects/under-construction/47963/)

Challenges and future impact

Within the framework of urban regeneration as a comprehensive and integrated vision and action which can address urban problems through a place-based approach which links the physical transformation of the built environment with the social transformation of local residents taking into consideration economic, physical, social and environmental conditions of an area, it is still early to assess the long-term effects of the projects described in the previous sections, in relation to the initial goals and final outcomes (such as attraction of private investment, young families with children, new economic activity, employment etc.). Nevertheless, discussions of relevant stakeholders and planners with the users of the areas highlight some important challenges in relation to the long-term impacts of the projects on the neighbourhoods and local residents.

In relation to the aim of the projects to attract private investment and initiatives in the areas it seems that it has indeed prompted an increased interest in rehabilitation subsidies. However, as pointed out by AEIDL there is concern that rehabilitation of façades only may lead to the deterioration of the repair works, in the case of empty dilapidated buildings or in the case of low-income owners and residents who do not have the means to complete the restoration.

One of the most important aims of the projects was the return of the past residents, the attraction of young couples with children and the establishment of new economic and third sector activities in the area. A growing interest of people wanting to buy or rent in the area has indeed been observed following the implementation of the first phases of the project and new residents are found in the areas. Also, people related to creative activities have started moving their workshops and officers back to these areas. Property values however, have since risen making the realization of the project’s’ aims more difficult. Finally both existing and new residents have been questioning the diversity of uses encouraged in their neighbourhoods asking for stricter control of the new cultural and entertainment uses settling in the areas.

The Planning and Managing Authority on the other hand has acknowledged that the integrated perspective has been quite underdeveloped during the current EU programming period and that the projects funded consisted mainly of basic infrastructure works (AEIDL 2012). For the planning of the next funding period they highlight the importance of empowering even more the local level and of ensuring that the appropriate mechanisms are in place for the actual participation of citizens from the early planning stages onwards.

Nevertheless, the projects have emphasized their integrated dimension and have successfully taken advantage of co-funding possibilities. National and local planning and managing authorities have been implementing individual sub projects as part of a wider strategy for the city and have pulled together different kinds of plans and programs from different levels, subsequently enhancing social and economic impact. The latter according to the people involved, has been wider than expected and positive results are already visible.

References

AEIDL (2012). Cyprus Nicosia Case study, European Commission.

Couch, C. (1990) Urban Renewal, London: MacMillan.

Charalambous, N. & Peristianis, N. (2002). “Cypriot Boundaries”, Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Working Paper Series, Vol.159:59-85, [Publisher: IASTE, Berkeley, University of California].

Marcuse, P. & van Kempen, R. (2000). Globalizing Cities: A New Spatial Order, Wiley and Blackwell.

Petridou, A. (2007). Rehabilitating traditional Mediterranean architecture. The Nicosia Rehabilitation Project: An Integrated Plan, Monumenta 02.

Roberts, P. (2000). The evolution, definition and purpose of urban regeneration. In P. Roberts and H. Skyes (eds.), Urban Regeneration A Handbook, London: Sage Publications, 9-36

Roberts, P. & Sykes H. (2000). Current Challenges and Future Prospects, Urban Regeneration A Handbook, London: Sage Publications, 295-314.

Tyler, P., Warnock, C., Provins, A. & Lanz, B. (2013). Valuing the Benefits of Urban Regeneration. Urban Studies 50(1) 169–190.

[1] In addition to these, a number of other projects (such as the pedestrianisation of important shopping streets) have been implemented with the aim of enhancing the attractiveness and functionality of the main commercial areas of the walled city. Furthermore, since 1991, the state’s Green Line Regeneration Program has funded municipal social infrastructure projects such as youth centres, supported entrepreneurs, and grant-aided the rehabilitation of shops and offices. Since 2001, the UNDP/EU-funded Partnership for the Future program has had a special section for the Rehabilitation of Old Nicosia, and has restored and promoted important historical and cultural landmarks.

Chapter 4: Neighbourhood regeneration, the case of Oslo

Viggo Nordvik,

NOVA, College of Applied Sciences,

Oslo and Akershus University, Norway.

Introduction

Regeneration can be about preservation or improvement of the quality of single housing units, or it can be about such improvements in a locally delimited area – in a neighbourhood. This short note is about area based regeneration initiatives in Oslo. Two interrelated features make this special in a European context. Firstly, the fact that owner-occupation is a dominating tenure across Oslo, also the parts that are candidates for area-based initiatives. In fact, the proportion of rented properties does not reach 50 percent in any township or neighbourhood in Oslo. Secondly, the fact that large parts of both activities and goals are not directly targeted towards physical aspects of the neighbourhoods that are ‘treated’.

Obviously improving quality can be (and often are) about upgrading or maintaining the physical quality of housing units and their surroundings. As argued by e.g. Nordvik and Turner (2014), neighbourhoods form a frame of our lives – in part because of who the neighbours are, and our choices of staying in or leaving one neighbourhood for another. Using a variety of social capital arguments Hoff and Sen (2005) forcefully argue for the importance of population composition for the quality of life in a neighbourhood. Hence, neighbourhood regeneration can affect the quality of life also through its effects on composition of the population. For this reason area based policy initiatives often aim to improve or sustain the social mix of some particular neighbourhood (Galster and Friedrichs 2015). Changing social mix is sometimes thought of as fighting against segregation along either ethnic and socio-economic lines, or both.

The Programme-approach

There are many examples of areas that have entered into serious negative and self-enforcing spirals of decline, multifaceted deprivation and even accelerating crime, where public agencies initiate regeneration programmes. Often, such programmes include physical upgrading of the housing stock, in particular this is an available option if (a larger part of) the housing stock consists of public housing. There are also examples of large-scale demolition programmes, one of the most infamous examples is the demolition of the Cabrini Green blocks in Chicago (Sampson 2012). One can also find examples of such drastic interventions in Europe.

Other interventions available in the menu of possible instruments of area based regeneration programmes are e.g. (financial) incentives for private investments, improving the quality of public services (e.g. schools) and investments in improvements of public spaces (notably easing the traffic burden on vulnerable parts of cities) (Andersson and Musterd 2005). One could also argue that facilitating coordination of private investments in an area, e.g. by setting up some kind of public-private partnerships, could be part of a regeneration programme.

The Oslo context

Spanning the last fifty years one can identify three major cluster of area-based initiatives in the Norwegian capital. The first one was the City-renewal programme of the 1970 and 80s. A main target of this was to eliminate sanitary substandard housing. The programme was successful as it almost entirely, eliminated the incidence of housing units without WC and bathroom facilities. Parallel to this, many of the rehabilitated properties were also transformed from rental housing into coops (Wessel 1996).

The next two programmes were targeted towards somewhat troubled parts of Oslo was the Inner city East programme in work from 1997 to around 2005 and the Groruddalen initiative which was launched in 2007 and is expected to continue until 2017. Neither of these two programmes were initiated in order to improve physical housing qualities in isolation. Rather, they were initiated because of observed differences in a set of indicators of living conditions and a concern for socio-economic and ethnic segregation. It is, however, probably correct to say that they did not address serious problems of deprivation – the observed differences were not dramatic (Aarland, Gjestland et al. 2014).

As already indicated Groruddalen is dominated by owner-occupation, mostly in the form of cooperatively owned housing units; the aggregate homeownership rate is 81 percent. This puts some limits to the design of the programme. The programme consists of four different sub-programmes targeted towards:

- Environmentally friendly transportation

- Green areas, sports and culture

- Area based intervention and local urban development

- Childhood and adolescence, civic participation, education and inclusion

Hence, one might summarise by saying that the programme intends to increase social capital in the targeted area. At the outset, the total budget of the programme was approximately 125 million Euros.

The programme is broad and includes a number of smaller and larger activities such as activities geared towards local youths and creation of activities and arenas that foster and showcase multicultural contact and understanding. Other activities and investments include setting up local malls, upgrading parks, recreational and sports facilities and creating safer walkways by installing street lights and upgrading sidewalks, underpasses and overpasses, see (Aarland, Gjestland et al. 2014).

Concluding remarks

It is not trivial to assess whether an area based initiative such as the Groruddalen programme has been successful or not. The ambitions of programmes can often be vague and the outcomes for the area itself and for its initial inhabitants can differ. Hence, it is not self-evident which criteria should be used for assessment of the success of a programme. Candidates for indicators used in evaluations are high school completion rates, reduced (white) flight and labour market participation. Obviously, the choice among these depends on the exact goal of the programme. We would also argue that changes in home prices often could be used as an indicator. Home prices captures the relative attractiveness of housing units in the regenerated neighbourhoods, as compared to elsewhere.

Another challenge in the evaluation of an intervention is the lack of evidence to the contrary. (Imbens and Wooldridge 2009). Even if one evaluates the situation on relevant indicators before and after the intervention, one cannot observe what would have been the case without an intervention. As we argued in the introduction, sometimes an area-based intervention is the response to rapid decline. Hence, stabilisation (instead of continued decline), could in some cases be a huge success of a programme.

References

Aarland, K., et al. (2014). Do area based intervention programs affect house prices? A quasi-experimental approach. Oslo.

Andersson, R. & Musterd, S. (2005). Area‐based policies: a critical appraisal. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 96(4), 377-389.

Galster, G. C. & Friedrichs, J. (2015). The Dialectic of Neighborhood Social Mix: Editors’ Introduction to the Special Issue. Housing Studies (ahead-of-print): 1-17.

Hoff, K. & Sen, A. (2005). Homeownership, community interactions, and segregation. American Economic Review: 1167-1189.

Imbens, G. W. & Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). Recent Developments in the Econometrics of Program Evaluation. Journal of Economic Literature 47(1): 5-86.

Nordvik, V. & Turner, L. M. (2014). Survival and Exits in Neighbourhoods: A Long-Term Analyses. Housing Studies (ahead-of-print): 1-24.

Sampson, R. J. (2012). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect, University of Chicago Press.

Wessel, T. (1996). Eierleiligheter: framveksten av en ny boligsektor i Oslo, Bergen og Trondheim, Universitetet i Oslo.

Chapter 5: Regeneration of multi-family buildings in local community of Zagorje ob Savi and user feedback

Sašo Medved, Suzana Domjan, Ciril Arkar,

Laboratory for sustainable technologies in buildings

Faculty of Mechanical Engineering

University of Ljubljana (UL), Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Introduction

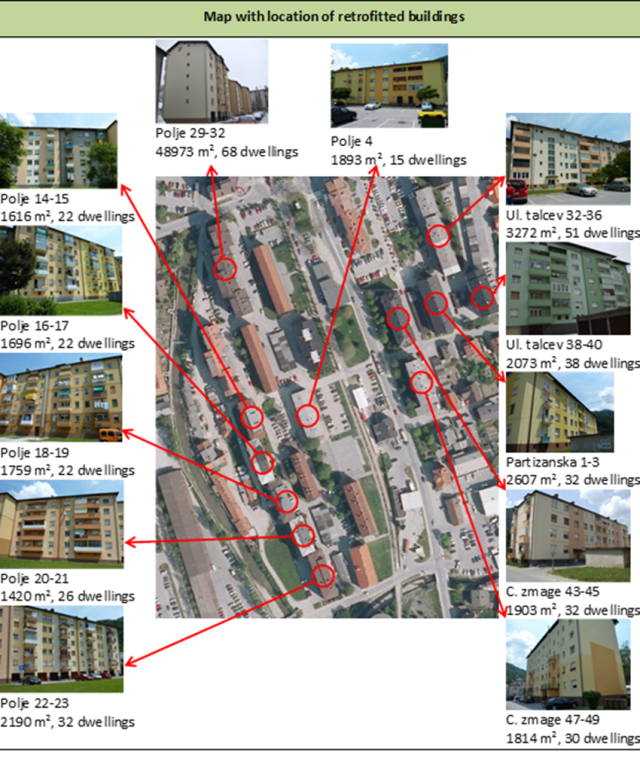

The EU-27 residential building stock has high potential for improved overall energy efficiency and reducing the greenhouse gasses emissions. It is estimated that approximately 25 billion m2 of floor space is used in EU, 75% of which is residential. Final energy consumption increased from 400 Mtoe to 450 Mtoe in last 20 years. Building sector represents the second most energy demanding sector and cause 36% all CO2 emissions (BPIE, 2011). Ambitious tasks regarding lowering energy consumption and CO2 emissions were set in EPBD, especially in EPDB recast presenting the Nearly Zero Energy Buildings requirements. Despite being more difficult to fulfil these requirements comparing to the new buildings, the retrofitting of existing buildings has larger savings potential. Retrofitting faces number of engineering challenges especially in the case of multi-family buildings. Successful retrofitting of multi-family buildings depends on several other factors, such as diverse ownership, low-incomes and lack of awareness. Those barriers can be overcame by large-scale local community driven activities, including awareness campaigns and best practices presentations. Below we present the example of the campaign, technical solutions and users’ responses for the case of large scale retrofitting of multi-family buildings in local community Zagorje ob Savi.

Local Community

The local community of Zagorje ob Savi is old mining community. In the year 1995, after 240 years of tradition, the coal mine was closed and, consequently, many jobs were lost. The unemployment rate is very high. The area is also one of the most polluted in Slovenia. The municipality is striving to lower energy consumption and the pollution that is caused by individual heating systems. Thirty years ago they built biomass district-heating systems. In 2007 programme of social multi-family buildings retrofitting started and until 2012 twelve multi-family buildings with 391 dwellings were energy retrofitted as part of the EU 7FP Concerto REMINING-LOWEX Project (Figure 5.1). The building-envelope, energy retrofitting covered façade thermal insulation, window replacement and, to a great extent, where it was technically feasible, thermal insulation of constructions for unheated basements and attics. The energy retrofitting also included the installation of heat-cost allocators, the installation of thermostatic valves and the installation of energy-efficient lighting in common areas (staircase, etc.) and in dwellings (energy-saving bulbs). Results of retrofitting are:

- the average U-value of the façades of the retrofitted buildings is lower than 0.23 W/m2K, which is 18% lower than that requested according to national regulations;

- on average more than 90 % of windows have been replaced; new windows have a U-value between 1 and 1.1 W/m2K, which is 30% lower than requested according to national regulations;

- ceilings under unheated attics were insulated with 25 cm of thermal insulation, having a U-value on average of 0.154 W/m2K, which is 23% lower than requested according to national regulations;

- where it was technically feasible, the floors over unheated basements were thermally insulated with 10 cm of thermal insulation;

- thermostatic valves installed on heat emitters;

- heat-cost allocators installed on heat emitters;

- adjustment of the heating-water temperature in order to lower the required heat power.

Figure 5.1: Location and area of the retrofitted multi-family buildings

Figure 5.1: Location and area of the retrofitted multi-family buildings

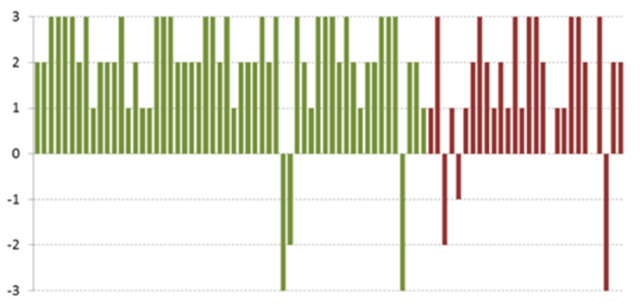

Results of retrofitting

The results of energy retrofitting was assessed by an analysis of the actual energy use for heating. The three-year period before retrofitting and the two heating seasons after retrofitting were analysed. The retrofitting measures were also checked using IR thermal scanning and blower-door tests. Both tests confirmed the good professional skills of craftsmen. The figure shows the average annual energy consumption for heating before and after the buildings’ retrofitting. The results of the analysis show that the specific final energy used for heating decreased, on average, by 47%, from an average of 119.6 kWh/m2a before the retrofitting to an average of 63.8 kWh/m2a after the retrofitting was completed (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2: The annual specific final energy used for heating per m2 of heated area before and after energy retrofitting; three years of data were collected for the period before the retrofitting and two-to-three years of data after the retrofitting

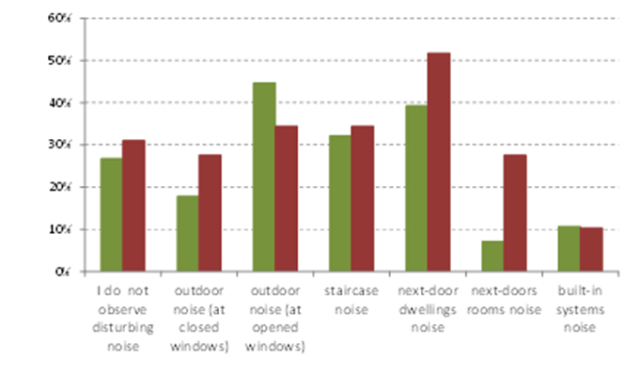

Users’ feedback

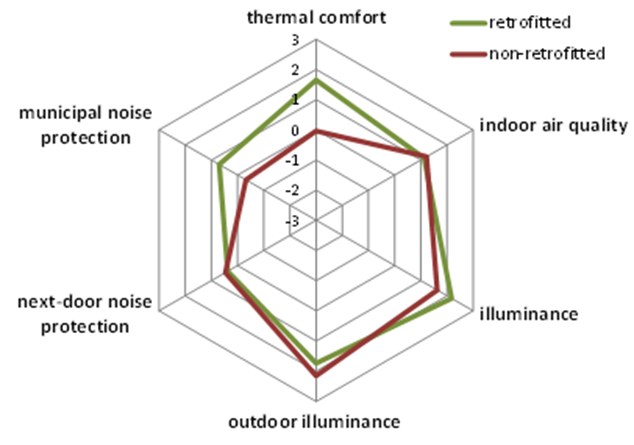

As retrofitting has a large influence on improved living comfort in the indoor environment, a survey of the residents in the retrofitted buildings was performed. The answers were compared to another group of residents living in a similar, non-retrofitted multi-family buildings in the same neighbourhood (Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3: Location of retrofitted and non-retrofitted multi-family buildings where the survey of indoor comfort was conducted (above); Polje 16-17 before and after retrofitting (below)

The survey was structured in such a way as to cover all areas of living comfort: thermal comfort, indoor air quality, lighting comfort and noise protection. At the end a section was added about the residents’ knowledge of energy efficiency and renewable energy-source technologies, with an emphasis on local systems (biomass district heating, etc.).

Thermal comfort